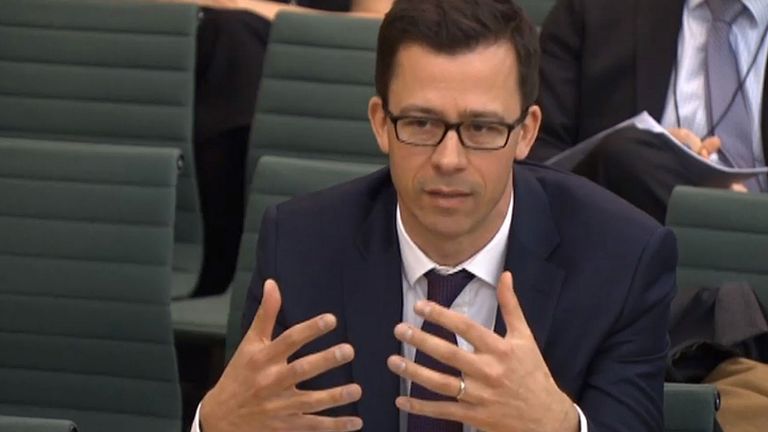

The UK’s unemployment rate could overtake the Bank of England’s (BoE) predicted peak of 7.5% as the coronavirus pandemic continues, one if its policymakers has warned.

Monetary Policy Committee member Gertjan Vlieghe said that, at the height of the pandemic, more than 30% of the private sector workforce was on furlough – the government’s programme to avoid mass job losses after non-essential shops were closed and the country was told to work from home in March.

More than two-thirds of those workers have returned, Mr Vlieghe said, but this still leaves more than two million people (9%) who are not yet back at work.

By point of comparison, he said, the global financial crisis saw a net 3.3% of the workforce lose their job, in the 1990s recession it was 3.8%, and in the 1980s recession it was 6.6%.

Mr Vlieghe said: “To be clear, we do not expect the 9% of private sector workers who are currently on furlough to lose their jobs.

“We expect many of them to either be re-employed by their current employer, or to find new work relatively quickly.”

“But our August central forecast was for unemployment to reach a peak of 7.5%, implying aggregate net job losses on the same scale as in the global financial crisis.

“The fact that redundancies are rising sharply and the number of vacancies is only at around 60% of its level at the start of this year makes it difficult to see a scenario where all of the remaining furloughed workers are reintegrated

seamlessly into the labour force.

“There is huge uncertainty about the scale of job losses, in both directions, but in my view, the risks are skewed towards even larger losses, implying even more slack in the economy than in our central projection.”

Last week, it was revealed that unemployment rose to a three-year high over the summer and there were more redundancies than at any time since 2009.

Despite this, Mr Vlieghe insisted it was “misleading” to think that, without government restrictions, the economy would have continued to function as normal.

“The hypothetical country that ignores public health but saves the economy does not and cannot exist,” he said.

“This is because the majority of the damage to the economy arises from restrictions that people voluntarily impose on themselves in order to protect their health, not from restrictions that the government imposes.

“In a country where the virus is more widespread, people will cut their spending more as they avoid crowded places, cutting back on travel, hospitality, leisure, culture, what we have started to call ‘social spending’.

“On the other hand, a country that puts in place a range of measures to contain the spread of the virus will experience less of an economic hit, as people are relatively more willing to engage in social spending if it is associated with much lower health risks.”

However, he warned that the trade-off between the economy and public health was more stark at the extremes – for example, keeping everyone at home until a vaccine was found would be good for public health, but would come at an “enormous cost” to the economy.