Pfizer boss’s shot in arm as lockdown wreaks havoc: We’ve stacks of vaccine ready to go when we get green light

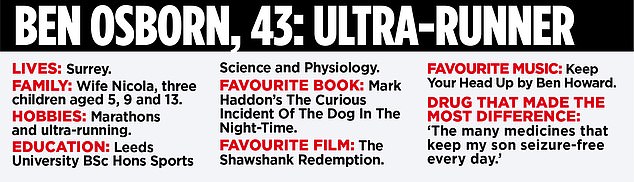

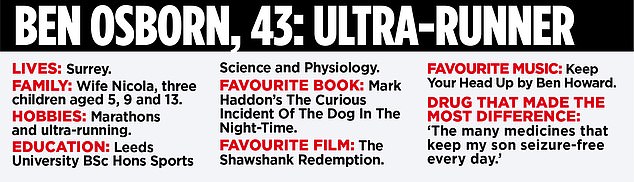

Vow: Ben Osborn, the UK boss of Pfizer

Ben Osborn is surprisingly chipper for a man carrying the hopes of a nation on his slim frame. The UK boss of pharmaceuticals behemoth Pfizer is champing at the bit to deliver the country the most unlikely Christmas present: a coronavirus vaccine.

A jab developed by Pfizer, with Germany’s BioNTech, is undergoing clinical trials and final-stage data is due imminently.

The public’s spirits were dampened last week by Andrew Pollard – the head of the Oxford vaccine project that is being driven by rival AstraZeneca – saying the first jabs would not be available until the New Year, with frontline workers prioritised. But Osborn gives more cause for optimism. ‘We’ve already got several hundred thousand doses sat in Belgium right now,’ he reveals.

‘I saw a picture of it the other day. It was great to see the first vial coming off the manufacturing line and it just brought a tremendous smile to my face to see all of this work over the last six or seven months actually now result in a product.’ He is quick to point out that nobody will get a vaccine until Pfizer and the authorities are absolutely sure they are safe. ‘I reinforce though, it’s still to finish the clinical trials, it’s still to go through the regulatory process but we do have physical product there available should we be successful,’ he says.

Participants as young as 12 are among the 44,000 taking part in the late-stage human trials.

So when can the public at large get a Covid jab? Osborn laughs: ‘It’s the question I’m asked every day by friends and family, it’s the question I’m asked by Government most days, we can only go as fast as the science allows us to. We are already manufacturing the vaccine at risk and at scale.’

Osborn is insistent no corners will be cut to rush the injection out, but if it’s given the green light, the company has vowed to make 100million doses available this year, and 1.3billion next. From the former, 40million doses are likely to head to the UK, with 20million patients taking two doses each.

He’s speaking from his home in Surrey over a video call, as outsiders are not allowed in Pfizer’s nearby labs amid tight Covid restrictions. The company, which has 2,500 UK staff, has ploughed nearly $2billion into its coronavirus programme so far, an investment which may have to be written off if the vaccine proves a dud.

On the subject of cures, 43-yearold Osborn says Pfizer’s scientists in Sandwich, Kent, combed their libraries at the onset of the pandemic for drugs that had not been fully developed that could tackle Covid. Now, early clinical trials have begun on humans for a specialised treatment which would be administered through an intravenous infusion, such as a drip.

Once proven to work, Osborn’s job will be to scale up its production. He says: ‘It’s tremendously exciting, the hope here is that we essentially come up with a medicine that disrupts the virus and ultimately prevents it worsening the condition of a patient.’

A rainbow picture on the wall is a reminder that Osborn’s own world view is shaped by the fact his eldest son has spent his life in the hands of the health service.

Stocking up: 100million doses will be made available and vaccine vials are already rolling off the production line in Belgium

George, 13, has a rare form of epilepsy which saw him suffer up to 40 seizures a day at the age of three. ‘I’ve lost count of the amount of times I’ve been in the back of an ambulance blue-lighting across to St George’s and various other hospitals around South-West London and the number of days he spent in the care of the NHS,’ Osborn says.

‘Thankfully due to some very innovative brain surgery at Great Ormond Street Hospital five years ago and the life-saving medicines he takes every day he is still with us and is thriving. He has got a lot of challenges, he has the mental age of a three-year-old, he requires a lot of care from the NHS and others, but I see first-hand how the NHS and biopharma industry have changed his life and our lives.’

Osborn’s two-decade career at Pfizer began as a drugs salesman, before climbing the ranks to his current role, held for 18 months.

Pfizer’s own image in this country took a hit in 2014, when the Viagramaker bullied its way on to the corporate stage with an attempted hostile takeover of British rival AstraZeneca. Its £55-a-share bid raised alarm in Westminster, and proved too cheap for shareholders. Astra has spent much of the last six years proving it was right to go it alone. Its shares, helped by a Covid kick, now sit at around £80.

‘It was a different point in time, we were looking more at large-scale mergers and acquisitions,’ Osborn recalls, adding that now Pfizer’s focus is on developing its own treatments in the lab and bringing them to market.

The company, headquartered in New York, appears on a decent track. Profits took a hit in lockdown as people worked from home and got fewer prescriptions and vaccines, but its Covid jab has been touted at around $20 a dose in the US. Osborn’s belief is that the future of the business, and the economy, hinge on people getting more vaccines for more conditions. ‘We’ve got to recognise the value of vaccination to public health in the first instance. We’ve got to show with the NHS the value of a healthy population to our economy.

‘Vaccination can help right from childbirth all the way through into old age but it’s a sad reality that many who should be vaccinated are just not presenting to the NHS to get their jab. There are many different vaccination programmes, and while we’re world-leading in many areas, we’re starting to see in some cases hesitancy around the value of vaccinations and we have to address that.’

Osborn is referring to the vociferous ‘anti-vax’ movement – people who refuse to get themselves or their children vaccinated amid mistrust of the health industry and fears over their safety. ‘I don’t condemn anyone for wanting to understand the safety and efficacy of our vaccines,’ says Osborn. ‘I point to history that shows the number of illnesses that we’ve been able to essentially eradicate because of vaccination.’ In August, the World Health Organisation declared Africa free of wild poliovirus.

The knife-edge outcome of the hunt for a Covid vaccine could burst the growing anti-vax campaign – or fuel its argument.