“I want a job, that’s what I really want. If I can work I’m happy.”

Kara Burgess is eloquent, educated, and unemployed.

She’s 29 and speaks passionately about her interests; she loves reading and caring for her pet dog. But there’s a weariness to her. It’s perhaps explained, at least in part, by her struggle to find work.

She’s been unemployed since 2018 when debilitating depression meant she had to leave her job in a call centre.

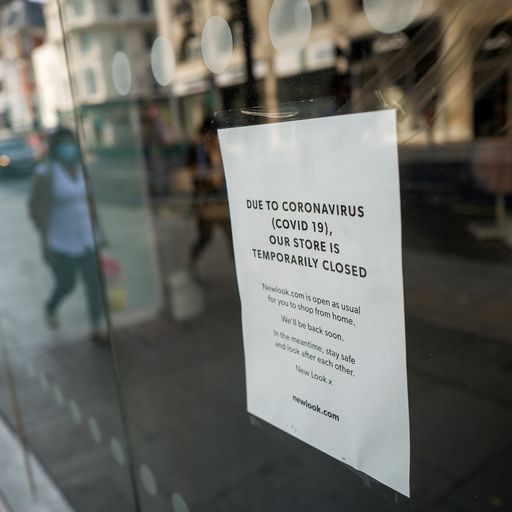

With professional help and hard work she’s now much better but coronavirus has thrown another huge hurdle in her way.

“I had an interview a week before we went to lockdown,” she explains. “I was getting good feedback, really really good feedback, to the point that we were certain I was going to get a job offer.”

But lockdown hit and she later learned the position had been withdrawn, the company like so many, couldn’t afford more staff.

“It’s really demoralising.”

“The biggest impact it will have is on my mental health,” she says. “My days are all the same at the moment, I’ll get up, walk my dog, feed my dog and then watch TV and Netflix.

“If it continues much longer, I can’t keep saying to myself ‘oh it’s just a short term thing to be going though.’ I want to work, I want to help, I want to earn. I’m ready to work, I really am.”

Ms Burgess is being supported by the Shaw Trust, the largest not-for-profit employment support service in the UK.

Amongst other things it helps deliver a variety of government programmes aimed at getting people back to work.

She’s enrolled in one of them, the work and health programme. It helps people with additional challenges to finding jobs such as the longer term unemployed, people with disabilities and people with mental or physical health programmes.

Hers is a familiar story at the trust, but the pandemic’s rewriting the rules.

Office for National Statistics (ONS) data released on Tuesday shows there are now nearly 700,000 fewer people in work than there were in March and 383,000 fewer job vacancies than at this time last year.

The official unemployment rate has risen to 4.1% and although that’s the highest it’s been in nearly two years, it’s still much lower than it was at the height of the financial crisis.

The government’s furlough scheme is still masking much of the problem and many fear the cliff edge when it concludes in October.

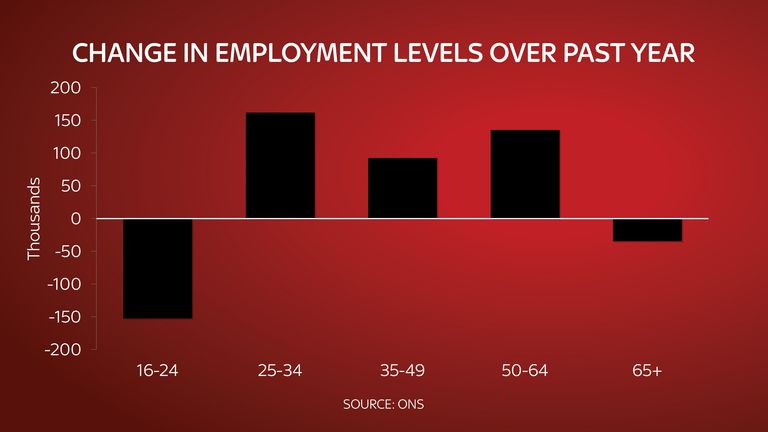

The ONS data shows that much larger proportions of workers under the age of 24 and over the age of 65 have lost their jobs in the last year.

The job market’s now crowded and many seekers are newly-redundant and experienced. The old, the young and the vulnerable are being squeezed.

It’s worrying for people like Jonathan Egan. He’s in his 50s and has worked for much of his life, but he left his job a few years ago to care for his elderly parents and since they died he’s struggled to get another one.

“I’m now up against a lot more people,” he says, “and also at the same time they’ve got very, very recent experience. It feels as if I’m being pushed to the back of the list.

“I’ve been shortlisted on several occasions and not got the position and you start to question ‘what have I done wrong’ or ‘will I get a position anywhere?'”

But although he’s staying positive the constant knock backs have taken a toll.

He said: “I’m old school, I deal with stress in a different way, to me I tackle things day by day. The only thing I have noticed about myself is that I no longer make long plans, they’re all short-term plans.”

He and Kara are two of more than 5,500 people supported by the Shaw Trust across central England.

Referrals to the service have actually been down during lockdown, they’d usually come mostly from job centres which have either been closed or preoccupied with the spike in claims for Universal Credit.

But staff know this drop in referrals doesn’t reflect reality. The government knows it too.

Support for the jobless was a major focus of the chancellor’s summer statement with £900m pledged for more, upskilled jobcentreplus work coaches and an extra £32m for the National Careers Service (also part delivered by Shaw Trust).

“We’re going to be busy, we’re preparing for that, we’re planning for that, we know it’s coming”, says Tanvir Ahmed, one of the support managers on the work and health programme.

“I think there’s still some anxiety out there from our staff team because there are a lot of redundancies, so are the jobs going to be out there for the people who come through our doors?”

The staff are broadly positive, they speak optimistically about new opportunities and growth markets, but there’s a nervousness too.

The employment support sector is just a sixth of the size it was before the last recession and many more people could need help this time.

Despite all the preparation they fear the vulnerable will still be most at risk.

“The disability employment gap which previously has been around 28% to people who don’t have a disability, is increasing vastly,” says Laura Burrough, the work and health programme’s regional operations manager.

“There are some demographics that the government hasn’t responded as quickly to, for example older workers or people with health conditions or disabilities.

“Absolutely, there is a need to get young people into employment, but we haven’t seen the government, at this stage, give enough attention or the same attention to varying cohorts that may face different challenges but significant challenges.”

For Ms Burgess, despite all the setbacks staying focused will pay off.

“It’s like hitting a brick wall, you keep running up against it until it cracks”, she says, “then you’ll see you see a little light, keep hitting it even more and eventually you’ll break through. It’s just perseverance.”