A very interesting statistic lurks within the National Accounts, published on Wednesday, which revealed that the UK economy contracted by 19.8% during the second quarter of the year.

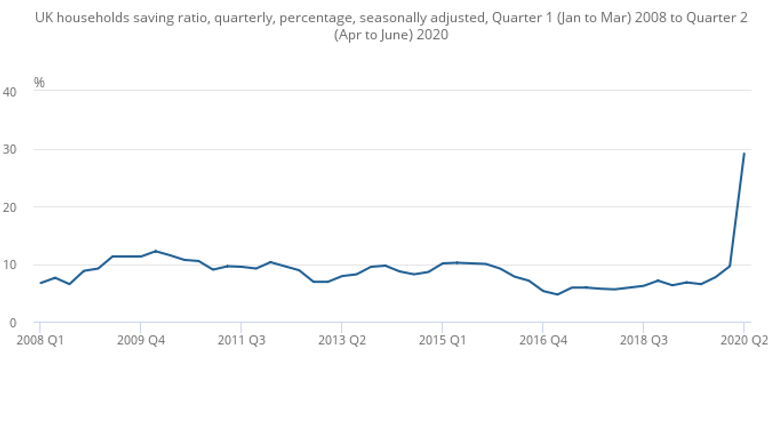

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) disclosed that the UK household savings ratio during April to June – the height of the COVID-19 lockdown – surged to 29.1%.

In other words, for every £100 received by a household – which includes salaries, benefits and any other income, such as dividends or interest – some £29.10 of that was saved.

The figure is absolutely extraordinary because, by and large, Britons are lousy savers compared to most of the developed world.

Even households in the US, a country widely assumed to be hooked on consumer spending and cheap credit, have typically saved more than British households in recent years. Only Australian households, among developed economies, are as spendthrift as those in Britain.

It is a trend that has accelerated during recent years. During the 1980s, UK households saved at least 10% of their income in all but one year of the decade – behaviour that persisted for most of the 1990s.

The household savings ratio began to fall in the late 1990s, when credit became more easily available, only rarely rising above 10% since then.

Between 1998 and 2007, the average was 8%, although this rose during the period around the financial crisis.

Since then, the ratio has continued to be comparatively low.

During the second quarter of 2018, for example, the ratio stood at just 5.9% and, during the second quarter of 2019, it was 6.8%. Slightly further back, in the first quarter of 2017, it fell to just 4.7%, a level not seen since the 1950s, a decade in which consumer spending took off as incomes rose and many previously rationed items became available again.

So for the figure to surge to a point where UK households are saving more than a quarter of their income is quite remarkable.

On the face of it, the explanation is obvious. The second quarter of this year saw most UK households in lockdown, with most shops, bars, hotels and restaurants closed. There were just not enough opportunities to spend money.

The ONS calculates that, during the quarter, households cut their spending by a record £80.5bn.

It added: “This is over nine times greater than the previous largest quarterly fall in household spending of this type. The reduction in spending is driven by large falls in expenditure on restaurants and hotels, transport – particularly air transport and motor vehicles – and recreation and cultural services.”

At the same time, while household spending fell sharply, household incomes did not fall at the same rate thanks to government support from programmes such as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme – or furlough scheme – and the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme.

But that is only part of the picture.

Another factor, well established over previous economic cycles, is that households save more during times of uncertainty and especially during recessions.

For example, the last big notable increase in the savings ratio was during the global financial crisis and the immediate aftermath, when it rose from 6.5% during the third quarter of 2008 to 12.2% during the first quarter of 2010. Similarly, the savings ratio rose during the recessions of the early 1990s, the early 1980s and the mid-1970s.

Much of this is psychological. If people think they are at risk of losing their job, or if they are concerned that the value of their home – the biggest single financial asset for most households – is going to fall, they will save more.

Similarly, as unemployment fell in 2017 to its lowest level for 45 years, so did the household savings ratio.

All this means that, in coming months, the household savings ratio will be an indicator watched even more closely than usual by economists as they try to establish what is likely to happen next in an economy traditionally heavily geared to consumer spending.

Allan Monks, economist at JP Morgan, told clients today: “Key to the outlook is the extent to which the saving rate will remain higher than usual due to voluntary saving, which reflects household caution over spending.

“It is too early to judge where things are settling, but the still very low level of consumer confidence suggests the saving rate is unlikely to return to its pre-pandemic level of just over 6%.

“While greater caution reflects fears over the virus, this is being compounded by concerns over a large rise in unemployment.”

There are already signs that Britons will struggle to stick to the savings habit.

The Bank of England reports that, in July, household borrowing rose for the first time in four months. The level of bank deposits also returned to more normal levels, indicating that, as lockdown ended, consumers began spending again, having saved aggressively in the preceding months.

And there will also be other disincentives to save, chiefly the fact that the Bank of England’s key policy rate is an all-time low of 0.1%, making it impossible for banks, building societies and other savings institutions to offer a meaningful savings rate.

Government-backed National Savings & Investments, an institution also favoured by many savers, has just slashed its rates.

While the spike seen this year in household saving is due to extreme circumstances, many people will hope that the savings habit becomes more established, even once the pandemic is over.

Industry estimates suggest that only around three in 10 working people have savings worth the equivalent of three months’ income or more, while as many as 12 million people – more than a third of the UK’s working population – are not saving enough for their retirement.

As Tom Selby, senior analyst at the stockbroker and investment platform provider AJ Bell noted today: “With lockdown strangling the ability of Britons to spend and the government’s furlough support scheme working to protect jobs and wages, it was inevitable those people lucky enough to remain employed would save more as a result.

“For those who are in this position it is vital they use this opportunity to pay off any high cost debts and build up a decent cash buffer if they haven’t already done so.”

Depressingly, there is already evidence to suggest that this extraordinary figure does not mark the renaissance of a savings culture in Britain. The Bank of England has recently highlighted a sharp divergence in behaviour, with households with incomes of less than £35,000 running down their savings during the lockdown, while households with more than £35,000 increased their saving.

Moreover, as the furlough scheme comes to an end, a rise in unemployment is inevitable, forcing growing numbers of people to run down what savings they have.

If the household savings ratio does remain at higher than usual levels, potentially weakening consumer spending, there are levers that the authorities can pull to try and change that behaviour.

The most striking of these would be a move to negative interest rates.