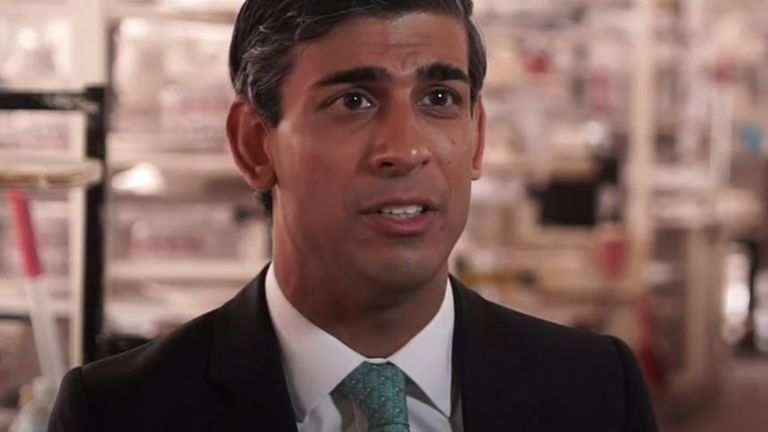

This isn’t widely known but Rishi Sunak’s furlough scheme was actually in some ways one of the fruits of Brexit.

Back before COVID-19, the Treasury had a number of options for policies to impose in the event of a catastrophic no-deal Brexit, one of which was to introduce something similar to a German system – the kurzarbeit.

Kurzarbeit dates back a century or so but really came of fame during the financial crisis when it helped shore up the German labour market even as many other countries faced massive increases in unemployment.

The principle is that if companies need to cut workers’ hours, the state will step in and help supplement their pay – hence the name, which roughly translates as “short-time working”.

Live updates on coronavirus from UK and around the world

In the fraught days before Boris Johnson imposed his first lockdown, Treasury officials dusted off the plan, made some adaptations and so the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme – or furlough to the rest of us – was born.

The UK furlough scheme actually went a fair bit further than kurzarbeit, with the state paying a bigger chunk of people’s salaries and insisting they stay at home in exchange (whereas the German scheme was more about topping up the wages of people working fewer hours).

Either way, the furlough was born and the rest is history: 9.6 million jobs supported and 1.2 million businesses helped.

Around three million jobs are reckoned to be supported even now, as the scheme is run down and the generosity of those government payments drops.

:: Subscribe to the Daily podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

All told, it has been one of the most expensive economic interventions in British history, with a total cost of £39bn pounds and counting.

That is more than the monthly NHS budget, so you can probably see why the chancellor has repeatedly said he will phase it out.

But that comes at a tricky time.

The latest measures of economic activity suggest that while the economy bounced back quite sharply from the initial shock of the virus and lockdown, that rebound may be losing steam.

The latest purchasing manager’s index seems to indicate that much of the momentum stopped in September, perhaps after the end of the chancellor’s Eat Out to Help Out scheme.

Few parts of the economy have been left untouched by the events of the past six months but some have been more affected than others.

Sky News’ analysis of job losses announced so far shows that aviation, retail and hospitality are the worst affected sectors.

Perhaps then it is no surprise that hospitality and aviation chiefs are among those calling for more targeted support in the coming months.

But what would that actually entail?

One option which looks likely is an extension of the business loans schemes which have lent more than £57bn so far.

They are currently due to come to an end this month.

But for some companies – especially those already with high leverage – that won’t be enough. They want an extension of the furlough scheme.

And while Mr Sunak does not want to bring back the full furlough scheme, he is considering returning to that original German model – a new kind of “kurzarbeit” or short work scheme for Britain.

Something less generous than the furlough, perhaps, which tops up the wages of workers whose hours have been cut – rather than paying them for staying at home.

In one sense it would be a more generous version of the Job Retention Bonus unveiled in the Summer Statement in July.

Strikingly, both the CBI and TUC have backed ideas along these lines – a relative rarity for both businesses and unions to be in the same court – which would help support about 50% of workers’ wages.

The attraction for the chancellor is that this would keep people in the workplace and support jobs that are still viable – but be much less expensive than the furlough scheme.

However, it does not do much for those who cannot even work part time.

Live entertainment, nightclubs, events and such sectors are facing a lost year, where they simply cannot operate at all.

The worry is there will again be more people left behind during this second wave of the virus.