A financial hub in a Methodist church and drop-and-go deposit points for small firms are among ideas being tested in cash-stricken communities.

Local people will also have access to cashback from convenience stores – even if they do no shopping.

Eight trials have been confirmed as part of a project to help solve problems with access to cash.

The closure of bank branches and cash machines has led to losses for local firms and has concerned consumers.

The plan for trials was drawn up in light of a major report warning that the country is “sleepwalking” into becoming a cashless society.

It concluded that eight million people in the UK rely on notes and coins, ranging from those without a bank account to people who are not comfortable with digital payments.

‘No shopping, no problem’

The eight trial areas, including remote communities such as the village of Botton, North Yorkshire, will test a range of ideas including pop-up Post Offices in small shops, and banking hubs in retail spaces.

Fifteen shops in four areas will trial the purchase-free cashback plan. Retailers will be remunerated for providing the service by payment services company PayPoint.

“It is critical that we find ways to protect the viability of cash, for consumers and communities alike,” said Natalie Ceeney, who wrote the access to cash report and is overseeing the projects.

“These pilots are designed to find sustainable ways to keep cash viable locally, which, if successful, can then be rolled out more widely.”

Reports on the progress, or otherwise, of the projects will be published in summer next year.

Ms Ceeney said that access to cash machines was not the only answer, particularly for businesses that needed to quickly deposit their takings. She said firm shouldn’t have to shut their doors during the day to drive to the nearest bank miles away in another town.

Making cash harder to spend

Not long ago there were two banks with branches in Ampthill. Then there was one. Now there is none. Currently just one cash machine is left to serve a population of more than 8,000.

Resident Brandon Wilson, 20, told the BBC in June that using cash helped him stick more rigidly to his spending plans to ensure he did not spend beyond his means.

“In general I try and budget my daily routine and having the physical money there means it is harder to spend than just placing a piece of card on to a machine,” he said.

Other project areas chosen for the trials include the remote Lulworth Camp, a military barracks in Dorset miles away from the nearest cash machine.

Small towns with thousands of residents which have seen bank branches or cash dispensers disappear are also included, such as Ampthill, along with Rochford, in Essex, Denny near Falkirk, and Cambuslang in Lanarkshire.

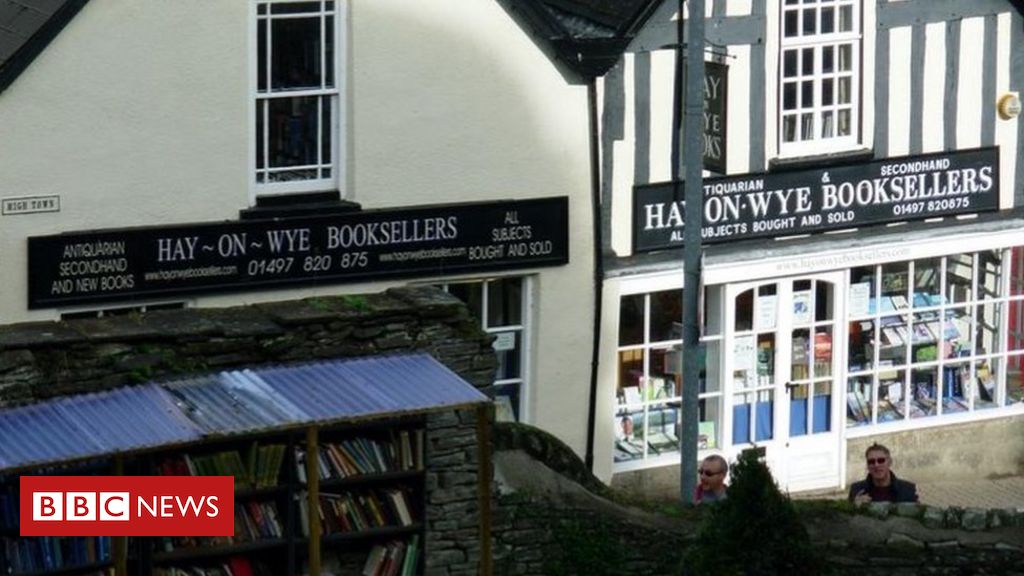

Burslem, in Staffordshire, is also on the list, as is Hay-on-Wye, which has a large number of bookshops and other small businesses but no bank branch to deposit notes and coins.

Millisle, in Northern Ireland, has recently been added as the eighth area to take part in the pilots.

Eric Leenders, from UK Finance, which represents the UK banks, said the sector was committed to access to cash remaining “free and widely accessible to those who need it”.

Martin McTague, from the Federation of Small Businesses, said: “While contactless undoubtedly marks the safest way to pay in the current climate, we have to ensure that coronavirus doesn’t cause us to sleepwalk into a cashless society we’re not ready for yet.”