The Treasury has hailed the furlough scheme as a success – hours after official figures showed the first rise in the UK’s jobless rate since the coronavirus lockdown.

Officials pointed to data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) that showed that more than half of the 9.6 million workers placed on the Job Retention Scheme at its height had returned to work by mid-August.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak argued the scheme, tipped to cost £54bn, had “done what it was designed to do” in saving jobs as COVID-19 forced most of the economy to be placed in effective hibernation.

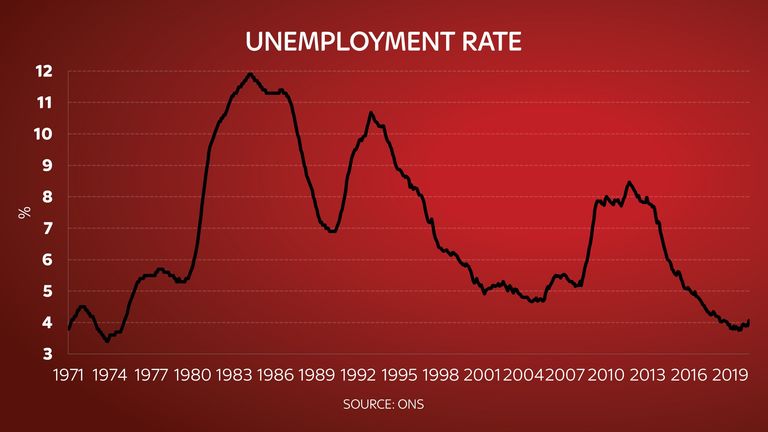

Earlier in the day, the ONS had reported that Britain’s unemployment rate hit 4.1% in the three months to July as the total number of jobless rose by 62,000.

The jobless rate was the highest in nearly two years and up from 3.9% a month earlier.

It is still yet to be fully illustrative of the economic crisis as the furlough scheme keeps the numbers down, but support for wages is to be fully withdrawn at the end of October.

There is a growing clamour among business groups, opposition politicians and unions for some form of targeted new support amid warnings from the Bank of England that the jobless rate could hit 7.5% by the year’s end, affecting three million people, as parts of the economy remain in the doldrums.

Mr Sunak has ruled out an extension to furlough but says he is open to “innovative and effective new ways to support jobs.

He said: “We were clear at the start of the pandemic that we couldn’t save every job, but the furlough scheme has supported millions of workers and we want to help employers keep people on.

“Our Job Retention Bonus will do exactly that, supporting businesses to do the right thing.”

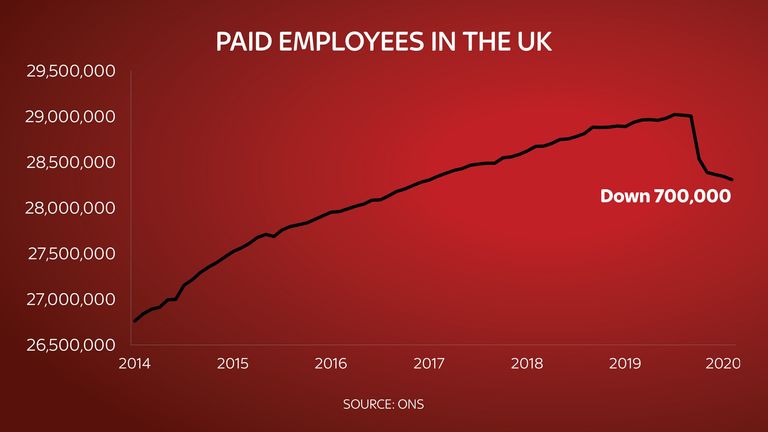

Payroll data released by the ONS showed that 695,000 fewer people were employed in August compared with March when the UK lockdown started – though after revisions to earlier data that was a smaller number than before.

Darren Morgan, director of economic statistics at the ONS, said: “Some effects of the pandemic on the labour market were beginning to unwind in July as parts of the economy reopened.”

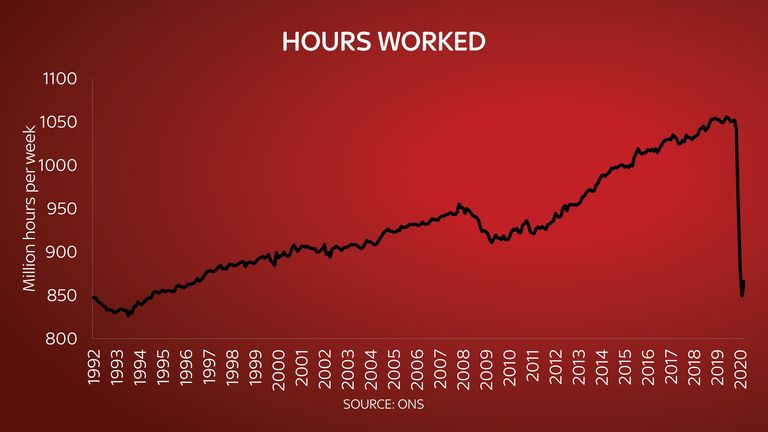

The number of people described as “temporarily away from work” – including those on furlough – fell in July though was still more than five million, while other measures including average hours worked and job vacancies also improved.

“Nonetheless, with the number of employees on the payroll down again in August and both unemployment and redundancies sharply up in July, it is clear that coronavirus is still having a big impact on the world of work,” Mr Morgan added.

The total number of unemployed for the three months to July was just above 1.4 million.

The number of people claiming unemployment-related benefits – which may include those with low hours or low pay – reached 2.7 million, up 121% since March.

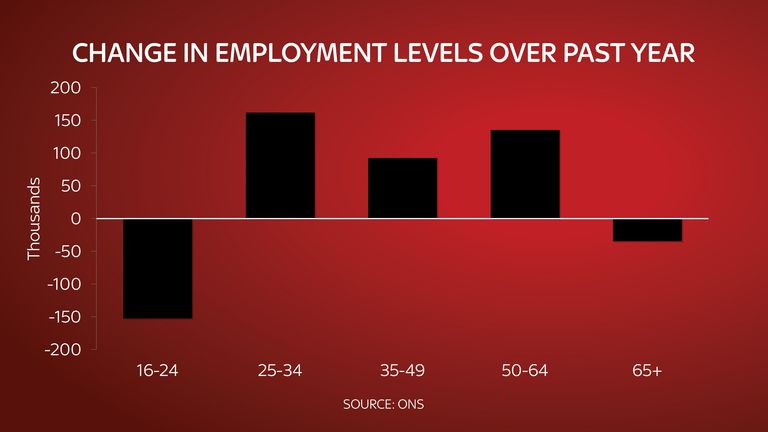

The figures also showed a stark contrast between the impact of the jobs crisis on different age groups.

The number of people in employment was 12,000 fewer in July than three months earlier.

But for those aged 16 to 24 years there was a fall of 156,000 – including a record decrease of 146,000 for those aged 18 to 24 – while jobs for those aged 65 and over fell by 92,000.

In contrast, there was an increase of 236,000 jobs for those aged 25 to 64 years, including a record increase of 67,000 for women in the 25 to 34 years age group.

A Sky News jobs tracker of publicly announced cuts shows that so far the aviation and retail sectors have been worst hit by the coronavirus crisis but many other parts of the economy including restaurants and sandwich chains also suffering badly.

Analysis: Still in the dark over jobs crisis

By Ed Conway, economics editor

Not for the first time, there is an air of unreality over the jobs figures today.

The unemployment rate is now starting to rise, up from 3.8% a few months ago to 4.1%.

But this is still far lower than it has been for most of recent history.

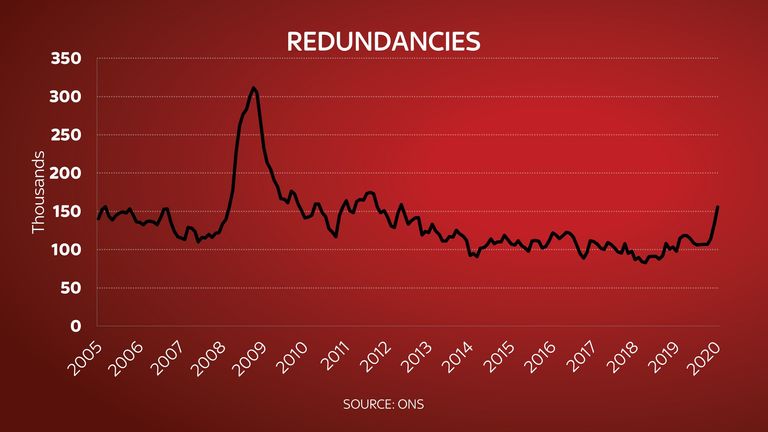

Redundancies are beginning to increase too, with more than 150,000 in the past three months – the highest rate since the aftermath of the financial crisis.

But the depressing likelihood is that this dramatically underplays the reality on the ground.

For the headline figures on jobs do little justice to the economic drama we know has happened over the past six months.

Millions of workers have been unable to work and have had their wages mostly paid for by the state and yet the overall employment total fell by only 12,000 in the latest three month period – because those jobs still technically exist.

Indeed, that is the whole point of the furlough scheme.

But while there may be some good news here – employment down less than expected, earnings also down less than expected (though still falling 1% a year) – it is just as likely that since we are in unprecedented times it has become harder than ever to make sense of the jobs market.

The Office for National Statistics themselves say that the figures are less reliable than usual because they are struggling to do the survey work they usually do to put together these data.

In other words, we are still somewhat in the dark.

We know millions of people were reliant on the furlough scheme and that a large chunk of them have gone back to work (though frustratingly the Treasury only informs us of the latter when it feels like it, unlike in other countries).

That is tentative good news.

What we do not know is how many of the remaining jobs will come back and how many will end in redundancy.

We do not know how high the unemployment rate will climb once the support has been entirely turned off (and note that even after the furlough scheme ends there is the back to work bonus in the following months, which is a not insignificant incentive for businesses to keep on workers).

So instead we are having to rely on some alternative measures of stress in the jobs market.

The ONS has a measure of how many employees are on companies’ payrolls, and this is down just under 700,000 since the beginning of the crisis.

The scale of this fall has actually been revised down since previous releases, but then it’s hard to know what to read into this.

The number of people claiming universal credit has also skyrocketed, more than doubling from 1.2 million to 2.7 million in the space of a few months.

Yet while some of that increase will be people who have lost their jobs, some is also likely to be people still in work but claiming extra support.

Again: we know the direction of travel but we still have yet to know how bad things will be.

For anyone who wants to get their head round the state of the labour market, this statistical fog is deeply frustrating.

But the likelihood is it perseveres for some time yet.