Royal Bank of Scotland employees altered customers’ files ahead of an independent review into mis-selling of toxic interest-rate hedging products – potentially helping the bank to avoid paying millions in compensation, documents reveal.

The files related to interest-rate swaps which the bank said would protect clients against rising rates. Instead, the bank generated huge profits and then, as rates plummeted, customers were saddled with crippling debts that in many cases led to bankruptcy.

In the case of a partnership of NHS doctors that had been sold a swap on a loan for building a new surgery, RBS staff altered information on their file ahead of the review carried out by KPMG, codenamed Project Rosetta.

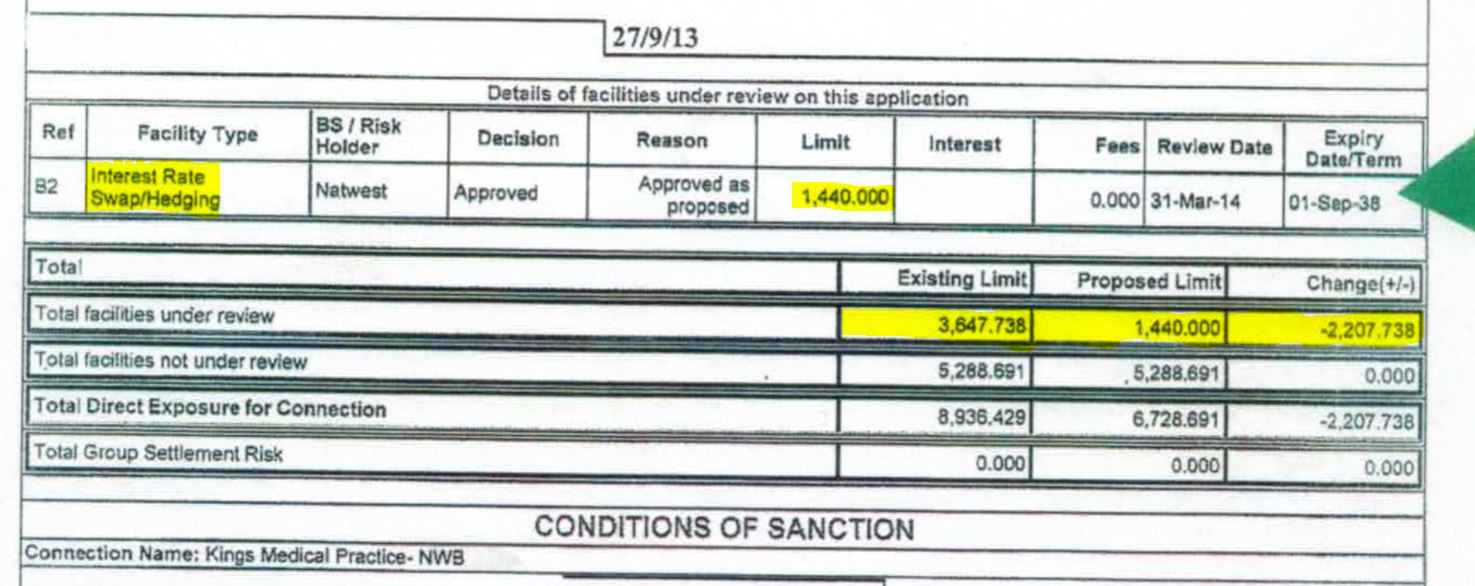

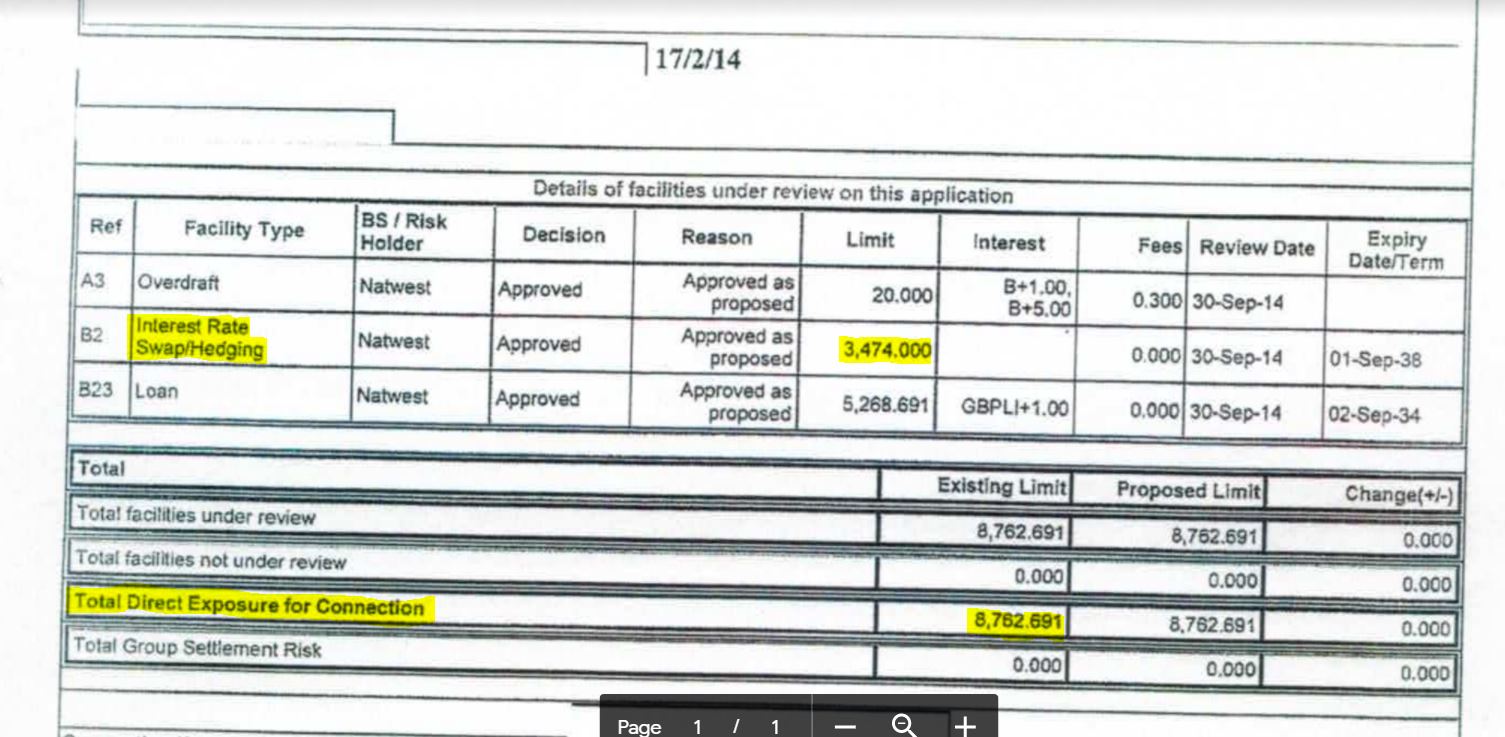

Internal files show that RBS expected the doctors to lose up to £3.7m on the swap it sold them. Days before the review, this figure was altered to £1.44m – then, shortly after the files had been submitted, the figure was increased to £3.5m.

Steve Middleton, a consultant for Modus Mediation who has been acting on behalf of the doctors, said thousands of customers have been wrongly denied billions of pounds in redress for mis-sold swaps.

He believes that hundreds of those were doctors’ surgeries, which RBS targeted to sell swaps to, hoping to secure stable long-term returns from taxpayers’ cash that the NHS used to cover GP surgeries’ rents.

According to Mr Middleton, the case raises the prospect that other files were tampered with ahead of a review that saw banks pay out £2.2bn in redress to customers. He believes that several billion pounds more should have been paid out.

Three financial experts who reviewed the files said there was no valid explanation for the changes or omissions.

A whistleblower who worked at RBS for 10 years told The Independent that they believe the documents were deliberately manipulated to mislead the reviewer in 2014 and that other customers’ files may have been tampered with in a similar way.

“This kind of behaviour ran right through the culture of RBS at that time,” the person said. “When I joined the bank, one of the first things they taught me how to do was to forge signatures on customers loan agreements and other documents.”

RBS, which has recently rebranded itself as NatWest Group, denies the claims and says the changes would not have impacted the review.

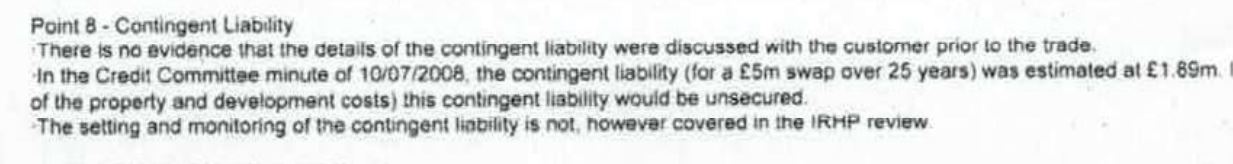

The documents also reveal that RBS took out millions of pounds of credit in its customers’ names without telling them to cover the losses resulting from swaps that the bank had recommended. This breached financial rules but, the documents show, regulators allowed banks to ignore this debt when cases were reviewed.

When the doctors complained, they were told that, while there was no evidence they had been told about this hidden debt, the “setting and monitoring” of the debt – which was referred to as a “contingent liability” – had not been considered by the review.

The review was overseen by the Financial Conduct Authority and should have been in line with financial regulations, which include the requirement to inform customers of all foreseeable risks.

In 2016, a senior FCA staff member who had worked on the review told Mr Middleton that contingent liabilities had been taken into account.

Yet the doctors’ files indicate in each of the 16,000 cases that were looked at, the regulator allowed banks to disregard the debts, even though they could potentially bankrupt customers.

When The Independent questioned the FCA on why this was allowed, the regulator declined to comment but said it “had not found evidence” to support Mr Middleton’s allegations.

The FCA was presented with evidence from the doctors’ case in July 2018 and in September that year its then chief executive Andrew Bailey – now governor of the Bank of England – said an investigation was under way.

Mr Bailey said the FCA was also looking into allegations that RBS had specifically targeted sales of swaps to NHS doctors’ surgeries. However, no response has ever been made public.

“The review was rigged against customers and in favour of the bank, all with the FCA’s knowledge and approval” said Mr Middleton. “Files that RBS sent to the review were manipulated, important information was missing, and then the standards of the review didn’t even comply with the rules.”

Sir Norman Lamb, a former health minister, said the evidence was “deeply shocking”, adding: “The fact that GP surgeries working within the NHS were targeted is pretty despicable.”

Commenting on the hidden credit lines, he added: “If it’s not criminal it ought to be. Yet no one appears to have been held to account for what happened. It robbed many people of good businesses without any ability to fight back. The whole thing horrifies me.”

Crippled with debt

In August 2008, five doctors who owned King’s Medical Centre in Normanton, West Yorkshire, took out a loan through RBS’ subsidiary NatWest for a loan of £5.2m to build a new surgery. They were told that they would have to take out a floating-rate loan and a hedging product to protect them from the risk of rising interest rates.

“At the time of the sale we had this super-slick presentation from RBS about hedging,” said Dr Jaz Walsh. “We were told we were protected by having this product in place against rising interest rates; that you were OK if rates went lower.

“We were frightened not to take it. We weren’t given another option.”

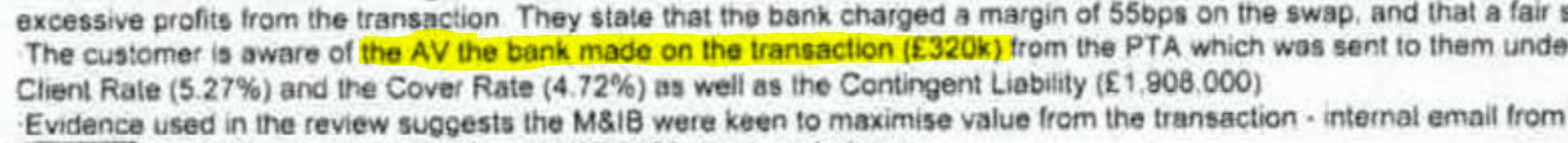

It was weeks before Lehman Brothers collapsed, financial markets were in turmoil and RBS’s internal models forecast that interest rates were about to plunge. That meant that the swap RBS recommended, fixing a rate of 5.27 per cent for 25 years, was costly for the King’s partnership and hugely profitable for RBS.

The bank made a profit on day one of £320,000. According to the whistleblower, the doctors’ bank manager, who was given targets to push the products, would have pocketed a bonus of “at least £30,000”.

The swap ended up costing the doctors £4m. Two of the partners were forced to work for more than two years past their intended retirement, while another went off work sick with long-term health conditions that had been exacerbated by stress. They ultimately had to sell the surgery in September 2018 to an investment fund based in Jersey, which now rents the building back to the NHS.

As it turned out, rates plunged even further than RBS had predicted. The potential costs, and the hidden credit taken out to cover those costs, surged to £3.7m, documents show.

The swap ended up costing the doctors £4m. Two of the partners were forced to work for more than two years past their intended retirement, while another went off work sick with long-term health conditions that had been exacerbated by stress. They ultimately had to sell the surgery in September 2018 to an investment fund based in Jersey, which now rents the building back to the NHS.

How it worked

According to the bank, the doctors’ combination of a floating-rate loan and the swap should have been equivalent to a standard fixed-rate loan. As interest rates fell, losses on the swap should have been cancelled out by lower payments on the loan.

However, there were key differences which RBS neglected to inform its customers about. If the doctors wanted to get out early – if, for example, they needed to sell the surgery, or one of the partners retired – they had to settle the “break cost”, a figure related to expected future losses on the swap.

Typically the cost of getting out of a fixed-rate loan early is between 3 and 5 per cent, which would have amounted to around £150,000 to £250,000. With the swap, the doctors faced a break cost of up to 70 per cent – £3.7m.

Given that the swap was over 25 years and two of the doctors were approaching retirement age, it was inevitable they would have to pay the break cost, as it was for thousands of customers sold swaps by RBS. From the outset, the swap was highly likely to saddle them with huge debts.

The doctors’ files reveal that, to cover these potentially massive losses, RBS took out extra credit in its customers’ names, similar to an overdraft.

Each of the thousands of customers who took out a swap had a hidden credit line that they never knew about.

RBS argues that these hidden overdrafts were merely an internal accounting measure, yet the debt was real and it was often secured against customers’ personal assets.

This had severe consequences for some customers. Loan agreements included a term that a customer’s total debt would not exceed a certain percentage of the value of their property. The hidden credit line meant that many customers were in breach of this term without even knowing.

In the doctors’ case, they took out a £5.2m loan. The hidden overdraft hit £3.7m, meaning that they were liable to the bank for £8.9m – on a property worth just £5.8m. Their loan-to-value ratio – a key measure of a borrower’s creditworthiness – was 153 per cent.

The doctors were personally liable for £3m secured against their personal property without their consent.

RBS could have bankrupted the doctors at any time from the moment they signed the agreement and gone after their homes.

The files show that the doctors’ bank manager had assessed the value of their homes at a combined £1.4m and cited this as a positive reason for approving the loan.

While RBS states publicly that these hidden overdrafts were not real debts, it called in those debts when it could.

The whistleblower who spoke to The Independent said RBS used the credit lines as a criteria to put hundreds of customers into its infamous Global Restructuring Group, before bankrupting them and selling off their assets. Often customers would not be told why this was happening. Instead RBS would “look for any reason”, such as a trivial breach of an obscure contract term to put customers into GRG.

Inexplicably, none of the reviews into swaps mis-selling or into GRG has ever considered the hidden credit lines as an issue. The FCA refused to state why this was the case and would not release the methodology of Project Rosetta.

“I was flabbergasted when it was explained to me how it worked,” said Sir Norman Lamb.

“It just seems like the most outrageous behaviour which the regulator, the FCA, has completely failed to confront. I am left simply failing to understand why the FCA hasn’t confronted this, hasn’t addressed it.”

Document tampering

Days after the file was sent for review, the credit line was increased to £3.5m. As the amount would have been linked to prevailing interest rates, the change could only be explained if rates shot up dramatically on one day in September 2013, then fell by the same amount shortly afterwards. But there was no such changes to interest rates.

The reviewer ruled that RBS had mis-sold the swap but the doctors would have bought it anyway, even if they had been properly informed – something the doctors described as “absurd”.

Days after the file was sent for review, the credit line was increased to £3.5m. As the amount would have been linked to prevailing interest rates, the change could only be explained if rates shot up dramatically on one day in September 2013, then fell by the same amount shortly afterwards. But there was no such changes to interest rates.

RBS said the change was the result of a “human error” by the doctors’ bank manager, and “made no difference to the subsequent review, which based its assessment on the risks at the point of sale and not at the point of review”.

The whistleblower questioned the bank’s explanation for the altered figures and said important information appeared to be missing from the files.

“It simply could not have been human error. It would have to have been a massive move in interest rates just before it went into review and has then been readjusted when it comes out. It just stinks.

“It is an extremely convenient coincidence that has massively helped the bank.

“Each time the rates went up or down significantly, Global Banking and Markets [the investment banking team that dealt with swaps trading], would have told the customer’s relationship manager [RM] to increase or decrease the credit line.

“The RM would then have to speak to the Credit team to agree this. They would then mark the facility to the right amount. They would all have known that this change made no sense. It never could have made any sense.”

Paul Carlier, a bank whistleblower with 30 years’ financial markets experience, said there was “no legitimate reason or cause” for the change, adding: “The drop in value would have had a huge impact on any figures that the skilled person or reviewer was seeing, especially in terms of appropriateness and damage to the customer.

Nick Stoop, an expert in financial derivatives at Warwick Risk Management, said he could not see “any legitimate reason” for the change. “The figures appear to have been manipulated for the purpose of the review,” he said.

“The effect of the reduction will have been to mislead the independent reviewer by understating the adverse impact the swap transaction had on the doctors’ credit position, including their loan-to-value ratio.”

Paul Carlier, a bank whistleblower with 30 years’ financial markets experience said there was “no legitimate reason or cause” for the change, adding: “The drop in value would have had a huge impact on any figures that the skilled person or reviewer was seeing, especially in terms of appropriateness and damage to the customer.”

When asked what work they had done to check that other customers’ files were not manipulated, an RBS spokesperson said: “Following a full investigation into these claims, which involved independent reviewers, the bank concluded that its treatment of King’s Buildings Partnership was entirely appropriate and revealed no wider or systemic risk.

“It remains our position that all of Mr Middleton’s claims on behalf of his client are entirely without merit and are refuted.”

An FCA spokesperson said: “The FCA extensively reviewed the Kings Building Partnership case but did not find evidence to support the allegations made and we can’t comment further.”There is an independent review into the FSA’s – and subsequently the FCA’s – approach to, implementation and oversight of the Interest Rate Hedging Products Redress Scheme ongoing and is due to be published next year.”